Subtotal: $81.00

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground, on soil, or on its food source. Toadstool generally denotes one poisonous to humans.[1]

The standard for the name “mushroom” is the cultivated white button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus; hence, the word “mushroom” is most often applied to those fungi (Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetes) that have a stem (stipe), a cap (pileus), and gills (lamellae, sing. lamella) on the underside of the cap. “Mushroom” also describes a variety of other gilled fungi, with or without stems; therefore the term is used to describe the fleshy fruiting bodies of some Ascomycota. The gills produce microscopic spores which help the fungus spread across the ground or its occupant surface.

Forms deviating from the standard morphology usually have more specific names, such as “bolete”, “puffball”, “stinkhorn”, and “morel”, and gilled mushrooms themselves are often called “agarics” in reference to their similarity to Agaricus or their order Agaricales. By extension, the term “mushroom” can also refer to either the entire fungus when in culture, the thallus (called mycelium) of species forming the fruiting bodies called mushrooms, or the species itself.

Etymology

Amanita muscaria, the most easily recognised “toadstool”, is frequently depicted in fairy stories and on greeting cards. It is often associated with gnomes.[2]

The terms “mushroom” and “toadstool” go back centuries and were never precisely defined, nor was there consensus on application. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the terms mushrom, mushrum, muscheron, mousheroms, mussheron, or musserouns were used.[3]

The term “mushroom” and its variations may have been derived from the French word mousseron in reference to moss (mousse). Delineation between edible and poisonous fungi is not clear-cut, so a “mushroom” may be edible, poisonous, or unpalatable.[4][5] The word toadstool appeared first in 14th century England as a reference for a “stool” for toads, possibly implying an inedible poisonous fungus.[6]

Identification

Morphological characteristics of the caps of mushrooms

A macro of a polypore mushroom

Maitake, a polypore mushroom

Identifying what is and is not a mushroom requires a basic understanding of their macroscopic structure. Most are basidiomycetes and gilled. Their spores, called basidiospores, are produced on the gills and fall in a fine rain of powder from under the caps as a result. At the microscopic level, the basidiospores are shot off basidia and then fall between the gills in the dead air space. As a result, for most mushrooms, if the cap is cut off and placed gill-side-down overnight, a powdery impression reflecting the shape of the gills (or pores, or spines, etc.) is formed (when the fruit body is sporulating). The color of the powdery print, called a spore print, is useful in both classifying and identifying mushrooms. Spore print colors include white (most common), brown, black, purple-brown, pink, yellow, and creamy, but almost never blue, green, or red.[7]

While modern identification of mushrooms is quickly becoming molecular, the standard methods for identification are still used by most and have developed into a fine art harking back to medieval times and the Victorian era, combined with microscopic examination. The presence of juices upon breaking, bruising-reactions, odors, tastes, shades of color, habitat, habit, and season are all considered by both amateur and professional mycologists. Tasting and smelling mushrooms carries its own hazards because of poisons and allergens. Chemical tests are also used for some genera.[8]

In general, identification to genus can often be accomplished in the field using a local field guide. Identification to species, however, requires more effort. A mushroom develops from a button stage into a mature structure, and only the latter can provide certain characteristics needed for the identification of the species. However, over-mature specimens lose features and cease producing spores. Many novices have mistaken humid water marks on paper for white spore prints, or discolored paper from oozing liquids on lamella edges for colored spored prints.

Classification

Main articles: Sporocarp (fungi), Basidiocarp, and Ascocarp

A mushroom (probably Russula brevipes) parasitized by Hypomyces lactifluorum resulting in a “lobster mushroom”

Typical mushrooms are the fruit bodies of members of the order Agaricales, whose type genus is Agaricus and type species is the field mushroom, Agaricus campestris. However in modern molecularly defined classifications, not all members of the order Agaricales produce mushroom fruit bodies, and many other gilled fungi, collectively called mushrooms, occur in other orders of the class Agaricomycetes. For example, chanterelles are in the Cantharellales, false chanterelles such as Gomphus are in the Gomphales, milk-cap mushrooms (Lactarius, Lactifluus) and russulas (Russula), as well as Lentinellus, are in the Russulales, while the tough, leathery genera Lentinus and Panus are among the Polyporales, but Neolentinus is in the Gloeophyllales, and the little pin-mushroom genus, Rickenella, along with similar genera, are in the Hymenochaetales.

Within the main body of mushrooms, in the Agaricales, are common fungi like the common fairy-ring mushroom, shiitake, enoki, oyster mushrooms, fly agarics and other Amanitas, magic mushrooms like species of Psilocybe, paddy straw mushrooms, shaggy manes, etc.

An atypical mushroom is the lobster mushroom, which is a fruitbody of a Russula or Lactarius mushroom that has been deformed by the parasitic fungus Hypomyces lactifluorum. This gives the affected mushroom an unusual shape and red color that resembles that of a boiled lobster.[9]

Other mushrooms are not gilled, so the term “mushroom” is loosely used, and giving a full account of their classifications is difficult. Some have pores underneath (and are usually called boletes), others have spines, such as the hedgehog mushroom and other tooth fungi, and so on. “Mushroom” has been used for polypores, puffballs, jelly fungi, coral fungi, bracket fungi, stinkhorns, and cup fungi. Thus, the term is more one of common application to macroscopic fungal fruiting bodies than one having precise taxonomic meaning. Approximately 14,000 species of mushrooms are described.[10]

Morphology

Amanita jacksonii buttons emerging from their universal veils

The blue gills of Lactarius indigo, a milk-cap mushroom

A mushroom develops from a nodule, or pinhead, less than two millimeters in diameter, called a primordium, which is typically found on or near the surface of the substrate. It is formed within the mycelium, the mass of threadlike hyphae that make up the fungus. The primordium enlarges into a roundish structure of interwoven hyphae roughly resembling an egg, called a “button”. The button has a cottony roll of mycelium, the universal veil, that surrounds the developing fruit body. As the egg expands, the universal veil ruptures and may remain as a cup, or volva, at the base of the stalk, or as warts or volval patches on the cap. Many mushrooms lack a universal veil, therefore they do not have either a volva or volval patches. Often, a second layer of tissue, the partial veil, covers the bladelike gills that bear spores. As the cap expands the veil breaks, and remnants of the partial veil may remain as a ring, or annulus, around the middle of the stalk or as fragments hanging from the margin of the cap. The ring may be skirt-like as in some species of Amanita, collar-like as in many species of Lepiota, or merely the faint remnants of a cortina (a partial veil composed of filaments resembling a spiderweb), which is typical of the genus Cortinarius. Mushrooms lacking partial veils do not form an annulus.[11]

The stalk (also called the stipe, or stem) may be central and support the cap in the middle, or it may be off-center or lateral, as in species of Pleurotus and Panus. In other mushrooms, a stalk may be absent, as in the polypores that form shelf-like brackets. Puffballs lack a stalk, but may have a supporting base. Other mushrooms including truffles, jellies, earthstars, and bird’s nests usually do not have stalks, and a specialized mycological vocabulary exists to describe their parts.

The way the gills attach to the top of the stalk is an important feature of mushroom morphology. Mushrooms in the genera Agaricus, Amanita, Lepiota and Pluteus, among others, have free gills that do not extend to the top of the stalk. Others have decurrent gills that extend down the stalk, as in the genera Omphalotus and Pleurotus. There are a great number of variations between the extremes of free and decurrent, collectively called attached gills. Finer distinctions are often made to distinguish the types of attached gills: adnate gills, which adjoin squarely to the stalk; notched gills, which are notched where they join the top of the stalk; adnexed gills, which curve upward to meet the stalk, and so on. These distinctions between attached gills are sometimes difficult to interpret, since gill attachment may change as the mushroom matures, or with different environmental conditions.[12]

Microscopic features

Morchella elata asci viewed with phase contrast microscopy

A hymenium is a layer of microscopic spore-bearing cells that covers the surface of gills. In the nongilled mushrooms, the hymenium lines the inner surfaces of the tubes of boletes and polypores, or covers the teeth of spine fungi and the branches of corals. In the Ascomycota, spores develop within microscopic elongated, sac-like cells called asci, which typically contain eight spores in each ascus. The Discomycetes, which contain the cup, sponge, brain, and some club-like fungi, develop an exposed layer of asci, as on the inner surfaces of cup fungi or within the pits of morels. The Pyrenomycetes, tiny dark-colored fungi that live on a wide range of substrates including soil, dung, leaf litter, and decaying wood, as well as other fungi, produce minute, flask-shaped structures called perithecia, within which the asci develop.[13]

In the basidiomycetes, usually four spores develop on the tips of thin projections called sterigmata, which extend from club-shaped cells called a basidia. The fertile portion of the Gasteromycetes, called a gleba, may become powdery as in the puffballs or slimy as in the stinkhorns. Interspersed among the asci are threadlike sterile cells called paraphyses. Similar structures called cystidia often occur within the hymenium of the Basidiomycota. Many types of cystidia exist, and assessing their presence, shape, and size is often used to verify the identification of a mushroom.[13]

The most important microscopic feature for identification of mushrooms is the spores. Their color, shape, size, attachment, ornamentation, and reaction to chemical tests often can be the crux of an identification. A spore often has a protrusion at one end, called an apiculus, which is the point of attachment to the basidium, termed the apical germ pore, from which the hypha emerges when the spore germinates.[13]

Growth

Agaricus bitorquis mushroom emerging through asphalt concrete in summer

Many species of mushrooms seemingly appear overnight, growing or expanding rapidly. This phenomenon is the source of several common expressions in the English language including “to mushroom” or “mushrooming” (expanding rapidly in size or scope) and “to pop up like a mushroom” (to appear unexpectedly and quickly). In reality, all species of mushrooms take several days to form primordial mushroom fruit bodies, though they do expand rapidly by the absorption of fluids.[14][15][16][17]

The cultivated mushroom, as well as the common field mushroom, initially form a minute fruiting body, referred to as the pin stage because of their small size. Slightly expanded, they are called buttons, once again because of the relative size and shape. Once such stages are formed, the mushroom can rapidly pull in water from its mycelium and expand, mainly by inflating preformed cells that took several days to form in the primordia.[18]

Similarly, there are other mushrooms, like Parasola plicatilis (formerly Coprinus plicatlis), that grow rapidly overnight and may disappear by late afternoon on a hot day after rainfall.[19] The primordia form at ground level in lawns in humid spaces under the thatch and after heavy rainfall or in dewy conditions balloon to full size in a few hours, release spores, and then collapse.[20][21]

Not all mushrooms expand overnight; some grow very slowly and add tissue to their fruiting bodies by growing from the edges of the colony or by inserting hyphae. For example, Pleurotus nebrodensis grows slowly, and because of this combined with human collection, it is now critically endangered.[22]

Yellow flower pot mushrooms (Leucocoprinus birnbaumii) at various states of development

Though mushroom fruiting bodies are short-lived, the underlying mycelium can itself be long-lived and massive. A colony of Armillaria solidipes (formerly known as Armillaria ostoyae) in Malheur National Forest in the United States is estimated to be 2,400 years old, possibly older, and spans an estimated 2,200 acres (8.9 km2).[23] Most of the fungus is underground and in decaying wood or dying tree roots in the form of white mycelia combined with black shoelace-like rhizomorphs that bridge colonized separated woody substrates.[24]

Nutrition

Mushrooms (brown, Italian)

or Crimini (raw)

Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz)

Energy 94 kJ (22 kcal)

Carbohydrates

4.3 g

Dietary fiber 0.6 g

Fat

0.1 g

Protein

2.5 g

Vitamins and minerals

Other constituents Quantity

Water 92.1 g

Selenium 26 ug

Copper 0.5 mg

Vitamin D (UV exposed) 1276 IU

Full Link to USDA Food Data Central entry; (exposed to UV light)

†Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[25] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[26]

Raw brown mushrooms are 92% water, 4% carbohydrates, 2% protein and less than 1% fat. In a 100 grams (3.5 ounces) amount, raw mushrooms provide 22 calories and are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of B vitamins, such as riboflavin, niacin and pantothenic acid, selenium (37% DV) and copper (25% DV), and a moderate source (10-19% DV) of phosphorus, zinc and potassium (table). They have minimal or no vitamin C and sodium content.

Vitamin D

The vitamin D content of a mushroom depends on postharvest handling, in particular the unintended exposure to sunlight. The US Department of Agriculture provided evidence that UV-exposed mushrooms contain substantial amounts of vitamin D.[27] When exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light, even after harvesting,[28] ergosterol in mushrooms is converted to vitamin D2,[29] a process now used intentionally to supply fresh vitamin D mushrooms for the functional food grocery market.[30][31] In a comprehensive safety assessment of producing vitamin D in fresh mushrooms, researchers showed that artificial UV light technologies were equally effective for vitamin D production as in mushrooms exposed to natural sunlight, and that UV light has a long record of safe use for production of vitamin D in food.[30]

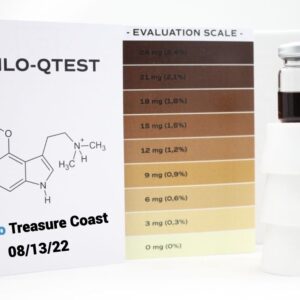

Mushrooms

$79.99 – $229.00

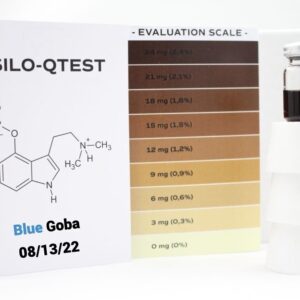

Mushrooms

$99.99 – $299.90

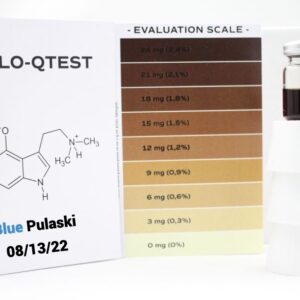

Mushrooms

$49.99 – $139.99

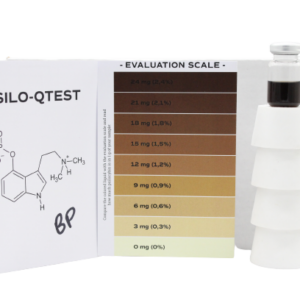

Mushrooms

$79.99 – $209.99

Mushrooms

$79.00 – $229.00

Mushrooms

$110.00

Mushrooms

$49.99 – $139.90

Mushrooms

$49.99 – $134.99

Mushrooms

$79.99 – $209.99

Mushrooms

$79.99 – $134.99

Mushrooms

$110.00

Mushrooms

$49.99 – $139.99

High Dose Edibles Bundle

High Dose Edibles Bundle